Friday Finds, Met Gala Edition: Tailoring Black Style

Who I'd wear to this year's Met Gala, and why it matters.

This year’s Met Gala theme, Superfine: Tailoring Black Style, is less a dress code than it is a thesis. It’s about Black brilliance turned outward—sharp lapels, wide-legged trousers, bold silhouettes, and the slow, gallant strut of someone who knows exactly how far they’ve come. It’s also about how much of modern style—especially tailored menswear—has been shaped by Black visionaries around the Atlantic, from Harlem to Kinshasa to Savile Row.

If I were miraculously invited, I wouldn’t be attending as a participant in that lineage. I’m not Black. I’m of mixed heritage—half-Mexican, half-Anglo Indian—and while I can’t claim this history as my own, I do feel a connection to it. The code-switching. The resistance. The refusal to be invisible. There’s a shared instinct, I think, in knowing that sometimes you have to dress like your life depends on it, because at one point, it actually did.

So if I were lucky enough to walk those steps this year, I’d do it in homage. And this is how:

As a centerpiece, I would wear a sculptural Kwasi Paul blazer by Ghanaian-American designer Sam Kwabena Boakye. It’s fine-tailored yet expressive, structured yet with a sly undertone; the denim strongly tied to the history of the African-American experience.

Underneath, a hand-dyed shirt from Post-Imperial, courtesy of Lagos-born Niyi Okuboyejo, whose prints draw on a West African textile ancestry in a modern register.

Pants? Definitely these upcoming fatigues from the young African/Chinese/Indian-American designer Connor McKnight. I find his pieces always have this relaxed simplicity that underlines a quiet authority.

On foot, a pair of limited edition Quebo slippers from Guinea-Bissau-born Armando Cabral—deerskin soft, hand-finished in Portugal, and stitched with just enough contrast to catch the eye. They say ease and elegance don’t mix, but Cabral proves otherwise.

Over my shoulders, one of Walé Oyéjidé’s oversized printed scarves from Ikire Jones, a sweeping and cinematic favorite of hip-hop icons including Nas and Jay-Z.

On the breast, a Ghanian brooch from Grace Wales Bonner, a British designer of Jamaican heritage, whose intuition has made her a household name among fashion enthusiasts for the past decade.

And a hand-crocheted hat from the jazz-influenced London-based Scottish-Jamaican designer Nicholas Daley to crown it all.

It’d be a look, yes. But more importantly, it’d be layered. Referential. In conversation.

As Monica L. Miller writes in Slaves to Fashion, Black dandyism is “about style as survival, elegance as armor.” In a world that often denies Black people the right to be seen, let alone celebrated, a well-cut suit isn’t just about aspiration—it’s self-respect weaponized.

This legacy stretches far and wide. From the Harlem Renaissance to Hard Bop, jazz greats from Duke Ellington to Miles and Coltrane didn’t just play cool—they looked the part too. Their clothing choices were deliberate, their silhouettes modernist, their presence undeniable. Zoot suits in the '40s made the body larger than life, a political statement in wool gabardine and swagger (one that my Chicano ancestors adopted, too). Across the Atlantic, the Sapeurs of the Congo (proselytizing “La Sape” or the "Society of Ambiance-Makers and Elegant People") turned colonial power on its head by dressing better than their colonizers—the King of Rumba Rock, Papa Wemba, even wore Yohji Yamamoto and Issey Miyake, flipping global fashion back on itself. And then there’s Ozwald Boateng: trained under tailor-to-the-rockstars Tommy Nutter to become Savile Row’s first Black tailor, and later the first Black creative director of Givenchy. His work has redefined what elegance means.

Monica Miller calls this “a self-consciousness about image-making that required the Black subject to mobilize his spectacular outlaw nature and turn society’s objectifying gaze into a social and cultural regard.” In other words, when the world reduces Black identity to a stereotype, fashion becomes a form of authorship. The body becomes a site of subversion.

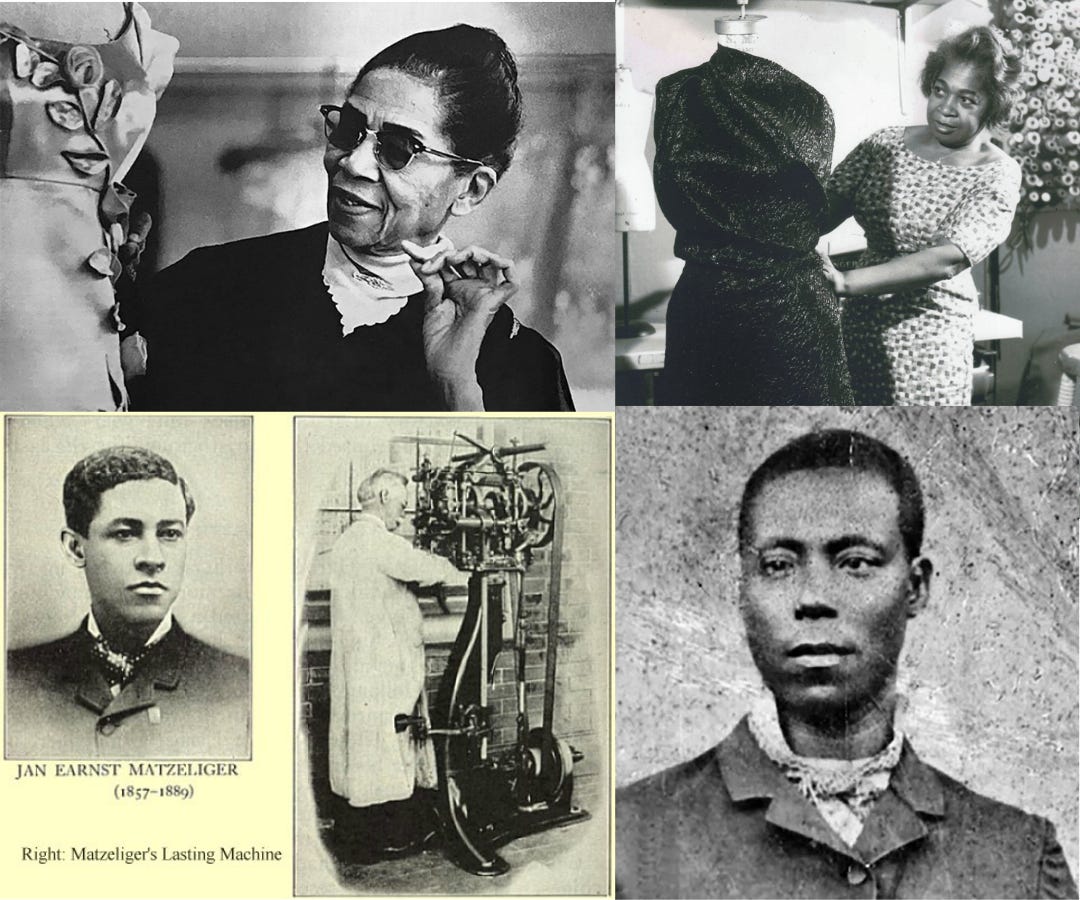

Even in the smallest details, the impact is there. The modern shoe-lasting machine—a foundational tool in contemporary footwear manufacturing—was invented by Jan Matzeliger, a Black man. Thomas Jennings invented the predecessor to the modern dry-cleaning process, which he called "dry-scouring," becoming the first African American to be granted a patent in 1821. The unsung fashion designer and costumer Zelda Wynn Valdes has been credited with creating the iconic Playboy Bunny costume. Ann Lowe made Jackie Kennedy’s wedding dress. These aren’t just footnotes. They’re a reminder: Black innovation isn’t peripheral to the fashion industry. It is the industry.

And today, a new generation of designers—as notable as Grace Wales Bonner and Pharrell, and as up-and-coming as Connor McKnight and Kwasi Paul’s Sam Boakye—are driving that legacy forward. They’re not just reviving tailoring; they’re revising it. Stylin’ out, as Miller puts it, is “both personal and political... about individual image and group regard.” These designers know the stakes, and they’re dressing us accordingly.

So yes, what I’d wear is a tribute—a layered, referential, deeply intentional expression of gratitude to the icons, the innovators, and the communities that have turned constraint into creativity and made menswear not just sharper but smarter, more soulful, and more alive.

I wouldn’t be dressing to be seen. I’d be dressing to say thank you.

Well said my man